After Shakespeare

Shakespeare and Newcastle upon Tyne collide with dazzlingly original results in this sequence of fifty-six poems inspired by many of the dramatist’s plays. Graham allows the rough energy of this Northern city to pulse through the book as many aspects of contemporary and predominantly low-life Geordie experience are viewed through a wide range of Shakespeare’s characters. Familiar figures from the plays reappear in bizarre guises so that these punchy, provocative and often humorous poems offer an unexpected and disturbing experience.

‘a remarkable evocation of a neighbourhood sinking into decay, yet peopled by odd, forgotten lives; outsiders, lovers and loners, washed up seamen and retired policemen, seen in the light of Shakespeare prototypes.’ New Welsh Review

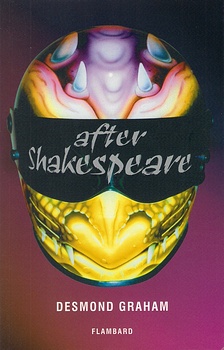

‘a gallery of urban low-life cleverly linked to Shakespearean analogues. Thus an old Frank Zappa fan and biker turned tattoo artist is an inner city Prospero… and a painter of Hell’s Angels crash helmets is Ferdinand, transforming reality in unpromising circumstances into art and exhibiting ‘a love of light where you would least expect to find it’. Graham, a poet who notices such things, has a way of finding those fugitive rays of light.’ Nicholas Murray, Poetry Wales

Prospero

he has covered the backs and shoulders

of half the former Gallowgate End

of the Toon Army and all the bikers

who sailed with him for the small time,

Prospero – Tattoo Artist;

his designs are legion: dragons wound

round the rib cage, purple tongues of passion

peeping out as snakes between the thighs;

a city side of Calibans he has transformed

with speech in the biceps, pectorals.

On Saturdays in summer you can hear

behind closed curtains sounds of the old days,

Zeppelin, Zappa, a whiff of dope and joss stick

clings to his leathers, a stream of pinks

and purples lights the evening sky.

Miranda long since left him.

Ferdinand wouldn’t give a toss

to work for such a wanker.

Gonzalo runs the perfect commonwealth

in the café on the corner.

He has one place left to cover:

the deft left hand he always uses.

The north wind blows a sound

like great waves falling from St James’s –

the Toon Army is calling for its freedom –

he lifts his implement and we hear buzzing,

the pigeons leave his attic by the broken pane,

right-handed he inscribes a single letter,

‘M’.

***

Rosalind

has legs long enough to make it

up the hill before anyone can tell

whether she is man or woman.

Rosalind ties up her hair and back,

puts on a beret, dun coat and ancient

trainers so no one knows her sex.

When Rosalind’s at home, alone,

high above street lamps, higher than pigeons

camped in the treetop below,

she lets her hair down like Rapunzel,

all the way, then handful over heavy handful,

climbs back up to reach herself.

Rosalind is a translator, translates

from silence into thought; translates

back all the gabbled chatter

which surrounds her in the daytime

into what it really means: she is mistress

of all languages extending beyond talk.

Then, in the morning, she will lace

her big brown boots, pin up her hair,

and take her whole self with her everywhere.