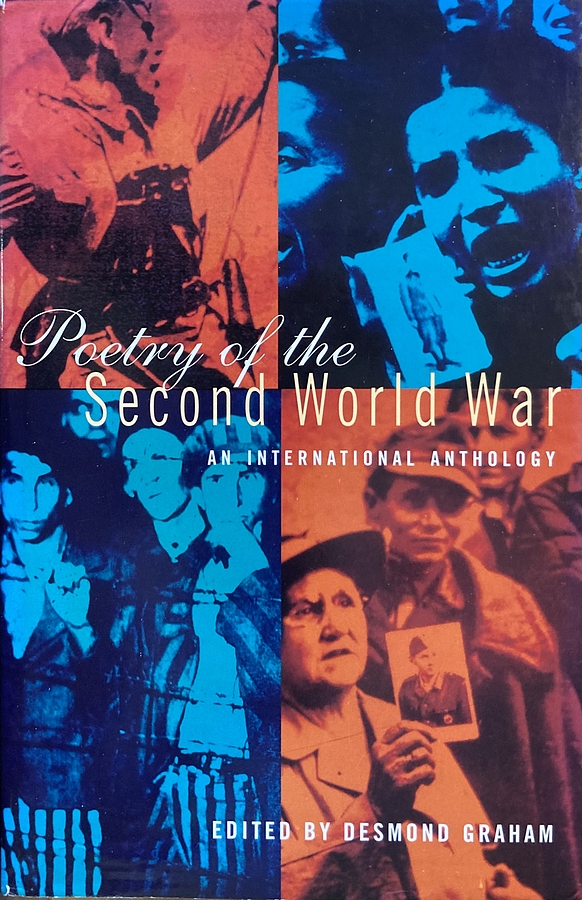

Poetry of the Second World War: An International Anthology

This anthology begins and ends chronologically. It starts with pre-war intimations: sensed by Miklos Radnóti in a mountain garden in Hungary in 1936; by Osip Mandelshtam, in 1937, a year before his own death in Siberia, as he contemplates the misfortune of a birth date ‘eighteen-ninety something’; by Charles Reznikoff, also a Jewish poet, on the seemingly safe west coast of America, receiving a letter which brings him to realize he may not be ‘with Noah and the animals,/ warm and comfortable in the ark’ but with those to be drowned. It ends with the ‘Aftermath’ when, in the words of the Austrian Ingeborg Bachmann, ‘War is no longer declared/ but continued.’

Between these extremes is a broad onward sweep, each section carrying a descriptive title taken from one of the poems within it: ‘By greatcoat, cartridge belt and helmet held together’ – conscription, military life, life in the Forces; ‘Boswell by my bed, Tolstoy on my table’ – responses from the edge, places not immediately in the thick of it, people still managing within the Blitz, people feeling they are on the war’s verge; ‘Wounded no doubt and pale from battle’ – the battlefields, in Europe, North Africa and Asia, on land, at sea, in the air; ‘At night and in the wind and the rain’ – the civilians caught up as refugees, under occupation, resisting, in forced labour, suffering the raids at Hiroshima; ‘Speechless, you testify against us’ – the genocide of the Holocaust; ‘I am twenty-four led to slaughter I survived’– the meaning of being a survivor; ‘For dreams are licensed as they never were’ – liberation, victory, recovery and continuation.

Each section is self-contained; as much as any aspect of the war could be said to have been so. Inevitably poems could take their place in one section or another, but their placing has never been without thought. At times within sections there is a certain chronological and experiential development but for the most part poems are arranged by theme and juxtaposition: sometimes aimed at contrast, sometimes harmony.

* * * *

from The Poetry Review Vol 85 No. 3, Autumn 1995 pp. 22-23

Miroslav Holub:

…Desmond Graham’s anthology, Poetry of the Second World War, is highly instructive. It brings together Germans and Russians, Americans and Japanese, Poles and Hungarians, Britons and Czechs, Romanians and Frenchmen, Italians and Irish. He discovers the hidden faces of well-known poets and adds some new names of people who experienced the war and who know. Above all, he demonstrates clearly, at times even drastically, that there is poetry after Auschwitz, though it is a little different. That even in poetry deeds speak louder than words, that the poetry of war and death is in fact Found Poetry, a record of the unutterable, a record in which abstraction, speculation and emphatic comment are more or less redundant.

…Matters of war and death simply shake off verbiage, they are too powerful for anything to match up to them, and in that sense they are themselves poetry, a frightful poetry. Unfortunately, there are not many non-frightful poetries.

Another simple statement from the other end of poetry and the planet (Randall Jarrell, ‘The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner’):

Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life,

I woke to black flak and the nightmare fighters.

When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.

In the context of the ‘recording poem’ the poetry of poetic nobility then falls into step with the records of people who only became poets as victims or fighters. Abraham Sutzkever, a partisan from the Vilno Ghetto:

Out of hunger

or out of great love –

but your mother can witness to it –

I wanted to swallow you, my child,

when I felt your small body cool

in my fingers . . .

. . . .

But I am not worthy to be your grave.

So I bequeath you

to the summoning snow,

the snow – my first respite

and you will sink

like a splinter of dusk

into the quiet depths

and bear greetings from me

to the small shoots beneath the cold

(Vilno Ghetto, 18 January 1943)

And the extremely sensitive compiler of the book immediately follows this record with Zbigniew Herbert:

… the dead flee the invasion of the living

they descend more deeply

lower down

they complain at night in the pipes of sorrow

they come out cautiously

drop by drop

once again they flare up

with a simple scratch of a match . . .

In this anthology it is not poetry that enhances reality, but reality that enhances the poetry.

…Desmond Graham, who is admirably well-read, has divided the book into nine sections, each of them headed with appropriate sensitivity by a quotation from the poetry in it, such as, ‘I lived on this age in an age’, or ‘By greatcoat, cartridge belt and helmet held together’, ‘At night and in the wind and the rain’, ‘For dreams are licensed as they never were’, or ‘War is no longer declared but continued’. Even the structure of the book is dictated by the logic of the basic human condition of being under threat, from outside and from within.

I don’t mean to say that it is good to have a war in one way or another so that we can reap some great poetry; I merely wish to say that it is one of those situations that leads to clarification, to a general elucidation of what constitutes poetry.

Translated from the Czech by Ewald Osers.